On Practice

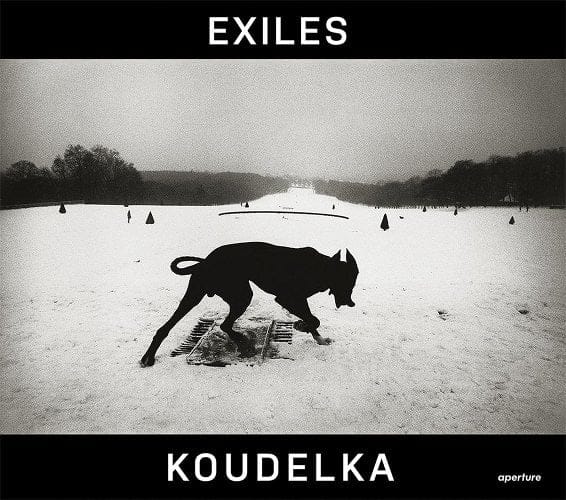

I heard a story about Josef Koudelka years ago and it made a deep impression on me. As you are likely aware, Koudelka, a Czech by birth, left his country in 1970, after it was invaded by Russia. An exile, he was to never settle down, forever roaming from place to place, sleeping on couches, floors, benches. In a 2015 interview published in Le Monde he said:

“To be in exile is simply to have left one’s country and to be unable to return. Every exile is a different, personal experience. Myself, I wanted to see the world and photograph it. That’s forty-five years I’ve been traveling. I’ve never stayed anywhere more than three months. When I found no more to photograph, it was time to go.”

The story I heard was that Koudelka was staying with a friend in a remote forest cabin somewhere in Europe. Upon waking, his friend realized that Koudelka was not in the cabin. Eventually he returned. "Where have you been?" asked the friend. Koudelka told him that he'd been out photographing the trees and the pine cones and the forest floor and anything else that captured his attention. He went on to say that he disciplined himself such that he daily practiced his craft no matter where in the world he found himself. To burn one roll of film daily was the minimum requirement.

Few of us are so dedicated, and admittedly Koudelka is a unique and brilliant photographic genius. Likewise, Artur Rubinstein was a brilliant concert pianist who enjoyed a long and productive career. Rubinstein continued to play after retiring professionally and reportedly practiced his scales everyday. Imagine achieving the height of your discipline, achieving mastery by any definition, and yet daily devoting yourself to the basic fundamental mechanics of your craft.

In her 1997 book, Mastery, Interviews with 30 Remarkable People, Joan Evelyn Ames asks cellist Janos Starker, "What are the most important elements in attaining mastery?" Starker responds:

Primarily it's discipline, self-control, and brain. Obviously the basic element is discipline....You have to discipline yourself to learn, to study, and practice, practice, practice.

I once gave a workshop to a group of young high schoolers interested in photography. I encouraged them to think of photography the way a musician thinks about music, that as a discipline ph0tography requires a similar devotion and discipline which includes a commitment to practice and study. I told them to think of their camera as their instrument, challenging them to know it inside and out. I suggested practices with the camera such that they could pick it up blindfolded and know exactly the function of each button, what each wheel and knob controlled. This is, I think, the photographic equivalent of practicing one's scales. (This is hard and can be confusing which is one reason I use simple basic cameras, stripping down my "instrument" to its essential functions.)

We live in a time when photography is taken for granted, which in turn has the potential to cheapen our craft. As serious photographers we must accept the challenge of rising above the fray, which means developing the discipline to practice towards a goal of excellence as best we are able. I've talked previously about the difference between being a photographer and being someone who takes pictures. Practice is at the heart of that distinction.

In a nutshell, it pretty much all boils down to discipline and practice.

Thanks for reading. If you find my musings to be of value, please consider referring this site to your photography friends.

You can find me at Doug Bruns, The Mindful Photographer